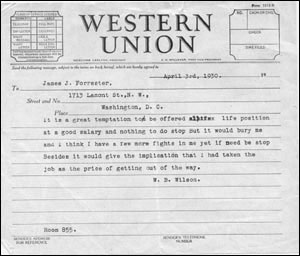

William Bauchop Wilson

First U.S. Secretary of Labor

“Wilson is a constructive man, a friend of capital as well as of labor, and one whom no just man need fear.”

— William S. Nearing, superintendent of Morris Run Coal Co., Morris Run, Pa., 1906

William Bauchop Wilson, 1862 – 1934

Introduction

Blossburg.org is a community site, intended to foster communication and interaction among Blossburg residents, area residents, and those who have moved away. It also is intended to be a living history project where stories about Blossburg can be told for wider audiences. This is the goal of the current William B. Wilson pages. This man helped shape the United States, advocating eight-hour workdays, strong unions, workers compensation, child labor laws, and workplace safety during his years of labor activism and political influence. In these pages you’ll read about his life, his beliefs, his impact on America, and see the images of that life. The web is a uniquely appropriate place for this and other history projects as it allows people from all over to collaborate, bringing disparate views and recollections together. If you have additional material to contribute, see errors or inconsistencies, please e-mail David A. Jones.

version 1.0.7 12/14/08

Coming to America

Arnot celebrated an annual Wilson Day. The five-page souveneir booklet shown above contained two photos of turn-of-the-century Arnot, a listing of the Wilson Day organizers, and the United Mine Workers of America logo.

William Bauchop Wilson was born in Blantyre, Scotland, April 2, 1862, the third child of Adam Black Wilson and Helen Nelson Bauchop Wilson. Two prior children, John and Hannah, each died at the age of four.

Two stories from Wilson’s unpublished autobiography illustrate his life in Scotland:

My earliest recollection runs back to a piece of childish mischief. We were living in a little village called Woodhall, on the banks of the Cather burn (brook), not far from Airdrie. It was a beautifully bright day and my aunt and my mother were taking advantage of the fine weather to wash and bleach the family linen. About the house was no place for a healthy boy who was too small to help and too large to be put to bed. My constant playfellow was about the same age as myself. We … wandered down to the brook where we paddled about and played and splashed each other until we were soaking wet from head to foot. On our way home we came upon a chimney sweep plying his trade in one of the cottages. The bags for holding his soot lay in a pile at the door… It was fine sport to wrestle and roll and tumble among the bags and see the dust fly up out of them. We were soon sticky with soot and blacker than the sweep himself. The washing was over at home. The sheets, pillow cases and table linen were spread out upon the grass, spotless and clean, bleaching in the sun. The sight of them took our fancy and we forthwith proceeded to decorate them with all kinds of fantastic figures. We threw ourselves down full length upon the linen and were filled with joy at the beautiful black imprints we made. We repeated the process up and down, crosswise and diagonally, with our legs and arms spread out like a cross, and closed up like a jack-knife, until there were few places of white cloth left big enough to make a mark upon….

Shortly afterwards, we moved to Haughhead in the suburbs of Hamilton. There I witnessed the only mine explosion I ever saw. I was playing with a number of children not far from the pit. In the midst of our games we were startled by a loud roar, and a great cloud of black smoke and rubbish shot out of the shaft as though propelled from the mouth of a cannon. Immediately there was consternation in the village. Women and children ran, excitedly screaming, to the pithead. Fortunately there were a number of experienced miners at hand. The mines had been shut down for repairs and most of the miners were at home. It was known, however, that there were eight men in the pit making repairs. A rescue party was organized at once. It was comprised of my father, two uncles and two other men. Shortly after they had been lowered into the pit, a second explosion took place. They were all given up for lost. Yet they were safe. Their search for the other men had taken them into a place where there was only one opening… and the explosion swept past them leaving them uninjured…This was in 1868, but young as I was it left a deep impression on my mind.

During a coal mine strike in Feb. 1868 in Haughhead, Scotland, Wilson’s family was evicted from their company-owned house. Although the strike was settled within a few weeks, the family did not have a place to live and roomed with two other families in an abandoned stable. Adam Wilson had two options: return to the mines and betray the cause of better working conditions for the miners, or leave Blantyre to find other employment. Adam Wilson sought work as a miner unsuccessfully in other parts of Scotland; the operators refused to hire anyone who was on strike in any other part of Scotland. After several more moves, Adam chose to emigrate to the United States to find work. With the meager savings he and Helen had accumulated in the Cadzow Cooperative Society, Adam sailed to New York in April 1870 leaving Helen with the children, William, Joseph, and Jessie, until he could save enough money to send for them.

Emigrating

Adam chose to settle in the bituminous coal mine region of Arnot, a small village in Tioga County, Pennsylvania, approximately three miles from Blossburg. After several months, Adam had saved and borrowed enough money to send for his family in Scotland. On August 27, 1870, Helen, the children and her father, John Bauchop, sailed from Glasgow, Scotland to the United States landing at Castle Garden, N.Y. about two weeks later. Wilson wrote of his first days in the United States:

…We expected father to receive us [at Castle Garden]. He was not there. Neither was there any message from him. All day long we waited and still no word came. We had no means to travel with and very little to buy food. When night came on the younger children were put to sleep on the benches. Mother sobbed occasionally, but under the circumstances her courage was great. About 9 o’clock at night, an agent came through the building calling mother’s name. He had an order for tickets over the Erie [Railroad] to Corning, N.Y., where father would meet us. We were bustled aboard a ferry boat and taken to the Erie station at Jersey City, and crowded into an immigrant train bound for the West. The next day we had a joyous reunion with father at Corning and took our first meal in a restaurant. That night about midnight we reached Blossburg. From there we rode in a lumber wagon on a log road through a dense hemlock forest to the new mining town of Arnot, our future home, where we arrived about 2 o’clock in the morning. It was a clear frosty night and the chill of the atmosphere was balanced by the beauty of the moonbeams shining through the trees.

The next morning we were out bright and early to get a glimpse of the new land that was to be our home. The first things that caught the eye were stumps and stones and rough board houses, not a very pleasant picture to one who had been accustomed to the well groomed surface of the valley of the Clyde.

Founded in 1866, Arnot, was the largest town in Tioga County by 1883 with a population of approximately 3,500 hailing from Ireland, Scotland, England, Wales, Sweden, Germany, and Poland.

Growing up in Arnot

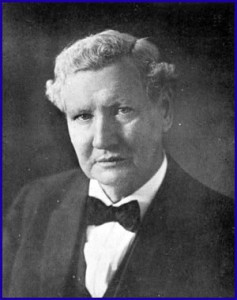

Cobbler shop owned by Hugh Kerwin (right) in Arnot, where Wilson formed a library and a debating society.

Wilson’s Education

A few days after arriving in Arnot, Wilson and his younger brother Joseph were enrolled in the public school. Wilson’s only education until this point was a year at St. John’s Grammar School in Hamilton, Scotland, where he had been an excellent student. His father, who was barely literate, and his mother, who was educated, hoped to provide William with a formal education. Although he had to leave school shortly after he began, Wilson bought and borrowed books on an array of topics to increase his knowledge and to read aloud to his father. Adam had a strong interest in philosophy, history and economics, which provided Wilson with a strong foundation for understanding the world and the position of the miners. Having once earned two dollars doing odd jobs around the community, he bought a second-hand edition of Chamber’s Information for the People and over the months that followed read it to his father.

Adam joined in the active debating sessions held in Hugh Kerwin’s cobbler shop and Wilson, as his constant companion and fact-checker, accompanied him. Wilson wrote, “As I look back on the group of men that formed our little circle in the early days at Arnot, many of them classed as illiterate, I am still amazed at the knowledge they possessed of many religious, social, economic, political, historical and scientific questions, their wisdom and tolerance in discussing them, and their wide acquaintance with good literature. It was a splendid school for any boy to attend.”

An avid reader, Hugh Kerwin kept a reading room and library in the back of his cobbler shop. Kerwin lent Wilson books from his library to take home and read. Wilson read every book in Mr. Kerwin’s library, and still was not satisfied. With Kerwin’s help, Wilson formed a library society and had the position of librarian, responsible for book selection and purchasing. Later, Wilson organized a debating society to gain public speaking skills. The club drew candidates for office during its political gatherings because it was known for the quality of its members’ debates.

Wilson’s democratic, capitalist political perspective was formed during these years. After gaining citizenship, Wilson’s father chose the Socialist party, but Wilson did not follow because he felt the two available extremes of anarchy or socialism did not allow for the “fullest and best development of the human race if carried to their ultimate conclusion.” Wilson strongly believed in the rights of the individual in a democracy and that those rights needed to be protected by government to ensure equal opportunity for all. He wrote, “Democracies are instituted for the purpose of giving to a majority of the people the power to determine [their collective future]…because it is recognized that certain things are purely individual in which no majority has any right to impose its will…” Wilson disagreed with the socialist stance of communal or state ownership of the means of production, believing that it inhibited individual development and expression.

Becoming a miner

Adam became ill with lumbago (a painful inflammatory rheumatism of the tendons and muscles of the lumbar region of the back) when Wilson was nine. He could still mine the coal but he could no longer pile it into the cars. Helen and Adam decided, with much regret, that Wilson should drop out of school to assist his father. Wilson loaded the coal into cars that his father had picked out of the rock while sitting on the mine floor. Eventually, his father taught him all aspects of mining. Wilson worked in the mine with his father for seven years.

In Nov. 1873, the mine owners cut wages, and then declared that the miners would not be allowed to cash in their company-issued script at the company stores until May 1874. The company stores would allow the workers to purchase up to their wages, but they could not have the remainder in cash. The farmers who sold their produce to miners were told they could only sell to the company stores. The farmers ignored the rule. The company then fired every worker who purchased from the farmers. At this point, the miners formed their first union, a local of the Miners and Laborers Benevolent Association. Only 11, Wilson joined as a half member. (Workers aged 16 and above were counted as full members.) The mine operators declared that no member of the union was permitted to work in the mines. The workers striked.

The company not only owned the means of production, but also the stores and the houses in which the workers lived with their families. The miners were evicted. Many stayed in Blossburg, the site of the nearest private, individually owned property. Throughout the mild winter, the miners continued to strike. They formed a store and worked with the farmers to bring food into the community.

Soon the rumor was passed around that the company was bringing in “Black Legs” to break the strike. One of the strikers was appointed to find the truth. And if it was true how would they come, from where and when. He reported that they were Swedes directly from Sweden, did not know a word of English and were coming by train. The miners had a meeting to decide how they would meet the “Black Legs”. Among their number was one Swedish man, Otto Johnson, who could talk Swed, having been born and lived in Sweden. They persuaded him to meet the train and tell them the exact situation. This he did as the train stopped beside the platform that served as freight and passenger station at that time. As the conductor opened the door he stepped up and greeted them in their native language. He explained the situation and answered their questions. After hearing what Mr. Johnson had to say the Swedes decided they did not want to take any miners job. They took a vote and informed the train men they were going back, they would not “Black Leg”. The company refused to return them on the train. The miners organized a band and lining up the Swedes, with Otto Johnson at their head and all the idle miners falling in, they marched the four miles to Blossburg. The miners helped procure work for most of them in machine shops, the foundry, the tannery and with farmers. The miners marched back to Arnot happy over a day well spent. By the beginning of March 1874, the company made overtures to settle. The strike/lockout was settled shortly, with the former wage rate and monthly paydays restored, the freedom to shop at non-company stores or with farmers re-established, and the houses reopened for occupancy. The Blossburg Coal Co. never tried to interfere with those basic freedoms again.

Later that year, Wilson decided to start a union for the boys who usually worked as trappers, opening and closing doors for ventilation in the mines. The boys followed Wilson’s lead when their wages were reduced by 10 percent and decided to strike. Wilson wrote:

We found [the foreman] inside… the driver shanty with his back towards a huge fireplace, his head bowed and his hands folded behind him as though warming himself, although, of course being June, there was no fire in the grate. We hesitated at the door and then I led the way in and acted as spokesman. “Mr. Dunsmore,” I said, “we have come to tell you that we are not going to accept the reduction in wages. We want the old rate back and if we don’t get it we’re going to strike.” He slowly raised his head and looked at us, then his hands came from behind him and in his right one he held the usual mine foreman’s yard stick. He caught me with his left arm and threw me over his knee and began to labor me with the yard stick. Every time he hit me with the stick he would exclaim, “I’ll strike ye, ye beggar!”… The other boys all ran off to their respective working places and when Mr. Dunsmore got through striking, I declared the strike off. His argument had been forceful and effective, but it was applied to the wrong part of my anatomy to be permanently convincing…. It helped impress upon my mind the fact that until working men were as strong, collectively, as their employers, they would be forced… to accept whatever conditions were imposed upon them.

Wilson later concluded: “Ever since that day I have not believed in the use of force to settle labor disputes. Instead of the use of force, what we need is the spirit of justice, of fair play, that will result in a permanent industrial peace.”

By 1876 there were only a handful remaining in the local union. With the decline in membership, Wilson was “pressed into service as secretary” of the local Miners’ and Laborers’ Benevolent Association. Wilson began to correspond with labor leaders around the country who expanded his knowledge and understanding of the labor movement.

The Next Twenty Years: 1880 – 1900

The back of farm house at Ferniegair Farm.

Eventually, Wilson’s activities as a trade unionist attracted the attention of the mine operators. In the spring of 1882, Wilson was a correspondent for the Elmira Telegram, a weekly paper, writing of the births, deaths, marriages, and other Arnot news. A series of articles appeared in the paper with an Arnot byline. Incorrectly suspecting Wilson as the author, the mine operator decided to fire him, using slack business as an excuse. Blacklisted for a time in Tioga County, Wilson went to Iowa to seek work and a pattern of irregular employment was established, although he continued his union activism.

From 1882 to 1900, Wilson traveled to many parts of the country looking for work and promoting unions. He dug ditches, worked as a lumber jack, wood chopper, bark peeler and log driver. He drifted West, and became a fireman on the Illinois Central Railroad for a time. At one point, he worked in a printing office in Blossburg setting type on a newspaper, where he learned punctuation, capitalization, and grammar. These experiences broadened his perspective on labor issues. Wilson wrote, “For some reason or another, I was unable to hold a job for more than a few weeks at a time. No fault was found with my work but my services were not wanted.”

On June 7, 1883, Wilson married Agnes Williamson, an Arnot resident and fellow Good Templar member, who was also born in Scotland. William and Agnes had eleven children. The Good Templars was a temperance organization. He wrote, “I would work at whatever I could find to do at home to keep my bills paid up and be ready to go whenever the call for help came… We lived in the most humble way and although my wife was a wonderful manager, we were often badly pinched for the means of living.”

During this period of labor activism, Wilson traveled extensively in Pennsylvania, New York, and Maryland assisting striking miners, establishing joint conferences between operators and miners (a precursor to the collective bargaining system), and organizing union locals. He was elected to the executive committee of the central Pennsylvania district of the Amalgamated Association of Miners and Mine Laborers, a part of the American Federation of Miners, and also to the position of District Master Workman of the Knights of Labor, another union with which he had been involved since his teenage years. In 1888, Wilson attempted to combine the two organizations into the National Progressive Union, but the Knights of Labor remained a separate organization. Finally, in 1890, he convinced the executive board of the Knights to meet with the Progressive Union to fully unite. Wilson became chair of the constitutional and by-law committee and on January 25, 1890, the United Mine Workers of America was formed. He was elected a member of the UMWA’s National Executive Board in 1891 and again in 1894. [Ed. note: The UMWA’s constitution, the committee of which Wilson was chair, specifically prohibited discrimination based on race, religion, or national origin, unusual for this time when Jim Crow laws were strictly enforced.]

As one of its first campaigns, the UMWA tried to create a movement for an eight-hour workday. However, the workers were not ready to undertake the battle and the issue was temporarily dropped. In 1896, Wilson was able to create a contract between miners and mine operators in central Pennsylvania that included a clause for an eight-hour day.

As he traveled, he stayed with miners who were willing to risk losing their jobs by hosting him, and many did. He was frequently jailed for his work, as were many progressive agitators of the time. Wilson advocated peaceful settlement of strikes, often interfering with militant workers’ plans to use force to settle a labor dispute.

Once he was tricked aboard a train by agents of the mine owners and taken to Cumberland, Md., thrown into jail on charges of conspiracy, but in three days they were forced to release him. Upon defying a court injunction Wilson said, “An injunction that restrains me from furnishing food to hungry men, women and children, when I have in my possession the means to aid them, will be violated by me until the necessity for providing food has been removed or the corporeal power of the court overwhelms me. I will treat it as I would an order of the court to stop breathing.”

After the coal strike of 1894, William once again found himself blacklisted and could not secure work in the mines. He secured a farm in 1896. He worked the farm in the summer and found various jobs throughout the area in the winter. In 1899 he was re-elected President of District No. 2, but resigned in May 1900 when John Mitchell, the legendary president of the UMWA appointed him to the position of Secretary-Treasurer of the United Mine Workers of America.

Wilson was elected International Secretary-Treasurer of the United Mine Workers of America in uncontested races for the next eight years and worked closely with Mitchell, the union’s fifth president.

United Mine Workers of America (1900 – 1908)

Strike of 1899-1900 As reported by The Blossburg Advertiser December 1898 through December 1899.

William B. Wilson worked closely as a friend and ally of UMWA president John Mitchell. Soon after Wilson took the secretary-treasurer position in 1900, the UMWA organized a strike that included Tioga County. At this point, Mary Harris “Mother” Jones came to Arnot to assist in the strike. It is interesting to the researchers that three of our primary sources, Babson’s biography, Wilson’s manuscript, and Flashbacks, a brief history by Phyllis Swinsick of the southeastern section of Tioga County, do not overlap in their tellings of the strike of 1899-1900, despite its national and local significance.

Babson writes, “…In behalf of the miners of Tioga County, Mr. Wilson took charge of the situation resulting from a prolonged lockout. A change of managers of a mine property and the abrogation by the new manager of the conference system…resulted in a lockout. It was a long and bitter contest in which Mr. Wilson, while steadily working to bring the opposing forces together and to re-establish the conference plan, sometimes lost the confidence of some of the more radical of the men he was leading.”

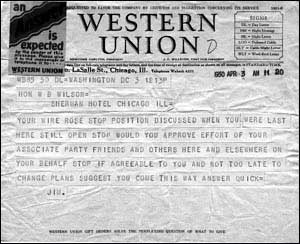

In her autobiography, Mother Jones wrote that the coal company tried to bribe Wilson :

After months of terrible hardships the strike was about won. The mines were not working. The spirit of the men was splendid. [United Mine Workers District] President Wilson had come home from the western part of the state. I was staying at his home. The family had gone to bed. We sat up late talking over matters when there came a knock at the door. A very cautious knock.”Come in,” said Mr. Wilson.

Three men entered. The looked at me uneasily and Mr. Wilson asked me to step in an adjoining room. They talked the strike over and called President Wilson’s attention to the fact that there were mortgages on his little home, held by the bank which was owned by the coal company, and they said, “We will take the mortgage off your home and give you $25,000 in cash if you will just leave and the strike die out.”

I shall never forget his reply:

“Gentlemen, if you come to visit my family the hospitality of the whole house is yours. But if you come to bribe me with dollars to betray my manhood and my brothers who trust me, I want you to leave this door and never come here again.”

The strike lasted a few weeks longer. Meantime, President Wilson, when strikers were evicted, cleaned out his barn and took care of the evicted miners until homes could be provided. One by one he killed his chickens and his hogs. Everything that he had he shared. He ate dry bread and drank chicory [instead of coffee]. He knew every hardship that the rank and file of the organization knew. We do not have such leaders now.” (p. 37-38)

Wilson created all the documents issued for publication to sway and maintain public sympathy to the miners’ cause, but he credits Mitchell with the success of the strike, “Through [the Republican National Committee], political pressure was brought to bear upon the financial interests and a settlement arrived at. It was much below that we had demanded and gave no recognition of the union, but we believed it better to confirm the improvements it gave than to take the chances of losing all by continuing the strike.”

Mother Jones, on the other hand, used more radical tactics in the 1899-1900 strike, probably appealing to the radical miners who were disillusioned with Wilson’s conservative actions. According to Swinsick, once Jones arrived in Arnot, she led the women in a parade to the mines where “they raised a howling ruckus,” using brooms, mops, pots, and pans. “The sheriff was called to stop them, but what man ever succeeded in intimidating a bunch of determined females? Scabs were driven off helter skelter and the women continued their loud and lively campaign day after day. And the men became converted to other tactics.”

The strike, the longest in Tioga County history at eight months, was finally resolved in Feb. 1900 after a hard winter.

Miners’ Advocate

When Wilson took charge of the treasury of the UMWA it contained $16,000 in poorly kept accounts. When he turned it over to his successor it contained over $1,027,000. By that time the UMWA had grow to have a membership of over 304,000.

Through the UMWA, Wilson sought protection from injury for workers, a shocking concept at the time. Wilson believed, “If a person wants anything, he ought to be willing to pay for the cost of producing it, including the cost of the accidents to human beings.” He used this argument in 1901 at hearings before a Pennsylvania Senate committee, resulting in the first Pennsylvania worker’s compensation laws, which became a model for similar laws across the U.S.

During the next large Pennsylvania coal strike in 1902, the UMWA advocated closed-shop policies, but the operators refused. The UMWA eventually lost on this point. Wilson explained the issue:Union men generally believe that there is no such thing as an open shop except on a small and insignificant scale. [Ed. note: Open shop: a workplace in which employees have the choice of joining the union and having its collective bargaining process. Closed shop: a workplace which all employees are required to be union members.] An operation either becomes all union or all non-union and is … promulgated principally by antagonistic employers who do not hesitate to discharge a union man whenever they find him in their establishment…. It is generally acknowledged that the aggressive power of a union in periods of industrial activity and its defensive strength during periods of depression maintain a higher standard of living not only for themselves but for non-union men in the same line of work than would be obtained with out it. Reasoning from that standpoint, they insist that common honesty should teach the person who receives the benefits brought about by the union to pay his share to maintain it. [Ed. note: Wilson’s claim of higher standards of living for non-union workers in an area where many are unionized continues to hold true in current sociological research. For references, e-mail Heidi I. Jones.]

Wilson also argued that corporations are fundamentally associations of capitalists who band together and hire collectively. He reasoned that workers should therefore also act collectively. “Any workmen who remain outside the terms of a collective bargain destroy the equality of the bargaining power to the extent of their numbers,” he wrote.

In 1908, Mitchell declined to run for the UMWA presidency again. Wilson became a candidate but lost by a small margin. He continued to be active in the American Federation of Labor (now part of the AFL-CIO) as a delegate and as president or secretary of the President’s Report committee. He noted that the union movement was involved in more than just issues of wages, hours, and working conditions: “community health; sanitation and safety; vocational diseases and prevention…; prenatal care; mothers’ pensions; child labor; protection of women and children in industry; compulsory education and free text books; vocational education; medical attention and hospital care for the injured…; employers’ liability and workmen’s compensation; the social aspects of wages and the hours of labor; the effect of immigration on the industrial, economic and political life of the nation; the virtues and faults of socialism and numerous other -isms…”

Congress

One of Wilson’s campaign posters.

Political History

Note: During one of his Congressional campaigns it was said that his opponent spent $1.11 for every vote received, while W.B. Wilson spent less than a cent apiece.

February 1884 – Elected township auditor (Bloss township). Wilson wrote about his first non-union elected office: “… In conjunction with my associates, [I] brought about a reform in the method of collecting taxes. An examination of the accounts disclosed a surplus of $300.00 in taxes collected… This was not a very large sum in itself, but quite large in comparison with the township budget.” He found that the company paymaster was also the township tax collector since the company owned nearly all the real estate in the township. By having the workers pay extra, the company didn’t have to pay as much tax to the township. Wilson was quickly able to clean up the situation.

1888 — Ran for representative in the Pennsylvania Legislature on the Union Labor and Democratic parties. He wrote, “The county was overwhelmingly Republican [Ed. note: And still is.] and there was never any hope of my being elected yet I succeeded in polling more than three times the normal Democratic vote. My expenses were less than $30.00.”

1892 — Ran for U.S. Congress as a Democrat. Lost in Tioga County Democratic convention due to political backstabbing by another Democratic candidate, John Sweeny.

1902, 1904 — Told party managers that he would run if uncontested for Democratic nomination for Congress. Party managers found other candidates.

1906 — Although Wilson again told party managers he would only run if unopposed for the Democratic nomination, he felt that “for the protection of my own reputation, [it was] necessary for me to fight for the nomination…. Under any other circumstances I would have given [the other Democratic candidate] my heartiest support. My ego told me that I was equally capable, progressive and strong, and in addition, I had a reputation to protect. To all attempts to get me to withdraw I replied that I was in the fight to the finish.” Wilson won the Democratic nomination for the Fifteenth Congressional District, including Lycoming, Clinton, Potter, and Tioga counties, after numerous ballots, but there were only a few weeks left before the election, not enough time to mount a solid campaign. He won the Nov. 2 election by only 384 votes, unseating Republican millionaire lumberman Elias Deemer of Williamsport, who was also president of the Williamsport National Bank and part owner of several Williamsport newspapers. He was only the second Democrat elected since the Civil War; Henry Sherwood of Wellsboro was the first. Served March 4, 1907 – March 3, 1913

Three factors clearly helped Wilson’s campaign:

- Deemer had created a feeling of mistrust because of his activities during the flood of 1889 when he was accused of stealing a lot of lumber that wasn’t his.

- The Democratic party in Lycoming County was particularly strong and quickly supported Wilson.

- Although Tioga County was heavily Republican, Wilson had very strong personal relationships with many workers and farmers. Deemer’s organization had overestimated their strength in the county.

During this term, Wilson served on the Patents Committee which revamped the Copyright Law. He also introduced a bill to appoint a committee to investigate mining disasters. Out of the appointment of this committee grew the founding of the Bureau of Mines and Mining, initially part of the Department of the Interior.

The Second Term, 1908

In this campaign he advanced no new issues, but simply told the people what he had done and what he had tried to do. The people of the district must have been pleased with his activities during his first term as they re-elected him by a much larger margin. Again, his opponent was Elias Deemer of Williamsport.

During his second term he served on the Census Committee which was in charge of the 1910 Census, the Committee on Patents and the Committee on Ventilation and Acoustics. “The latter [was] a dead committee,” Wilson wrote, “although I felt that the poorly ventilated condition of the House would have justified the committee in being active and aggressive in moving for a reconstruction of the ventilating system.” The patents committee face issues similar to that of the copyright committee upon which Wilson had served during his first term, particularly the way in which to protect the material recorded on phonographs. [Ed. note: These issues are still under debate, now in the form of protection of digital material such as this web site.]

The Third Term, 1910

During the campaign of 1910, Wilson was a delegate to the British Trade Conference, and was there during all but three weeks of his campaign. In the previous campaigns it was said he was successful through his campaigning and personality. But the campaign of 1910 showed that he was successful because so many people loved and trusted him. Although far away in England, without power to campaign or take care of his own interest at home, he still won in a Republican district over a Republican candidate by about 3,000 votes.

With this election the Democrats came to power in Congress and Wilson was appointed Chair of the Labor Committee. Wilson championed the cause of a separate Department of Labor, as these concerns now fell under the jurisdiction of the Commerce and Labor Department, one that would give the Secretary of Labor the power to act as mediator or appoint commissions of conciliation in trade disputes. Workers had agitated for a separate Labor Department and secretary since 1865. A commissioner-level position had been created in the 1880s, then folded into the Department of Commerce. As a part of Commerce and Labor, the bureau had been neglected in favor of business owners. The bill was sent to President Taft who did not sign it until one hour before the end of the legislative session. Wilson also served on the Committee for Mines and Mining and the Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries. In February of 1912 Wilson introduced a bill to improve the conditions and training of the Merchant Marines. In the House this bill became known as the Wilson Seamen’s Bill. He also worked on the successful passage of an eight-hour work day for women in the District of Columbia.

The Fourth Try, 1912

Wilson was unsuccessful during his fourth campaign as there were not only the Republican and Democratic candidates, but a Socialist and a Prohibition candidate as well. With the division of votes going to four candidates, Wilson lost by 568 votes, and the Republicans once again were in office.

Wilson thought he was through with politics in 1912, but a strong movement developed in 1914 and again in 1918 to make him Governor of Pennsylvania. It was only the active interference of President Wilson that prevented W. B. Wilson from being nominated in 1914. When the delegation came to Washington urging the President to release him from the office of Secretary of Labor, President Wilson replied:

“Gentlemen, you can much more easily find a suitable candidate for the Governorship of Pennsylvania than I can find a suitable candidate for the office of Secretary of Labor.”

Tried Again, 1914

In 1914 William B. Wilson made another unsuccessful bid for the House of Representatives to the Sixty-fourth Congress.

Senate Run, 1926

William B. Wilson was an unsuccessful candidate for the U.S. Senate in 1926.

Secretary of Labor

W.B. Wilson and his staff of directors

March 5, 1913 – March 5, 1921

On March 4, 1913 the Department of Labor was created by an act of Congress and Wilson, as Chairman of the Committee on Labor, was instrumental in its passage. Wilson was appointed by President Woodrow Wilson to be Secretary of Labor in the newly formed cabinet post. W.B. Wilson took office on March 5, 1913.

The purpose of the Department of Labor shall be to foster, promote and develop the welfare of the wage earners of the United States, to improve their working conditions, and advance their opportunities for profitable employment.

When Wilson took charge of the Department of Labor there were 2000 employees and four bureaus, all of which had been previously housed in the Department of Commerce and Labor. The four bureaus were Children, Immigration and Naturalization, Labor Statistics and a Division of Conciliation. With World War I, Wilson quickly made the Department of Labor an important piece of the administration by coordinating the movement of 6 million workers from non-essential to essential industries and then returned them once the war was over. Many of the activities of the Department of Labor, except the regulatory work that would eventually become very important, trace back to that period: the employment services, employment of women, retraining of veterans with disabilities, fair employment for minorities, and labor-management relations.

On a lighter note:

Wilson was the first cabinet member to have a government issued motor car.

1921-1934

William B. Wilson resigned from the office of Secretary of Labor at the end of his term, March 5, 1921. On March 4, 1921 he was appointed a member of the International Joint Commission to prevent disputes regarding the use of the boundary waters between the United States and Canada, and served until March 21, 1921, when he resigned. The records the researchers have consulted are unfortunately sketchy on the last part of Wilson’s life.

The telegrams above illustrate Wilson’s commitment to integrity.

In 1926 he made a bid for election for the U.S. Senate and was defeated. Wilson contested the election and below is the Record of the Committee on Rules and Administration and Related Committees that pertain to the election.

In 1926 he made a bid for election for the U.S. Senate and was defeated. Wilson contested the election and below is the Record of the Committee on Rules and Administration and Related Committees that pertain to the election.

17.28. William B. Wilson – William S. Vare of Pennsylvania, 69th – 71st Congresses (1926-29): This complex case initially revolved around questions of campaign financing, particularly in the 1926 Pennsylvania Republican primary, but expanded during the course of the investigation into several precedent-setting areas. In that primary, Vare defeated the incumbent, George Wharton Pepper. Wilson was the Democratic nominee against Vare in the general election, and after his defeat, he contested Vare’s election on the grounds of corrupt practices, illegal registration and voting, and other irregularities. In a break from customary practice, the case was investigated by a special committee of the Senate as well as by the Committee on Privileges and Elections. In 1929, it was determined that neither Vare nor Wilson was entitled to the seat, and, ironically, the seat was filled when Governor John S. Fisher appointed Joseph R. Grundy to the remainder of the term. Grundy, a wealthy manufacturer, was a central figure in the investigation of the primary for allegedly contributing approximately $400,000 to Senator Pepper. Records (4 ft.) of the case are in the committee papers of both the 70th (70A-F20) and 71St Congresses (71A-F24) and include minutes and notes of committee meetings; unpublished transcripts of hearings (vols. 1-20 in 70A-F20 and vols. 21-25 in 71A-F24; vol. 21 missing); unpublished transcripts of arguments, May 23-29, 1929 (71A-F24); and petitions and briefs of candidates, Senate resolutions, campaign expenditure data, exhibits presented at the hearings, and other records (71A-F24).

He had worked as an arbiter in Illinois coal fields before his death.

William Bauchop Wilson died aboard a Washington, D.C.-bound train near Savannah, GA. on May 25, 1934, after a month’s stay in Florida. Blossburg and the whole United States paid their last tribute to Wilson on June 3, 1934, when services were held at the Ferniegair Farm in Blossburg. Wilson is buried along side his wife, in Blossburg’s Arbon Cemetery, not far from the burial site of his mother, father, daughter Nellie, and grandfather John Bauchop. Also buried next to Wilson is his son Adam, Adam’s wife Gertrude, and his daughter Agnes Hart Wilson who died during her own race for the U.S. Senate in 1928.

The Family

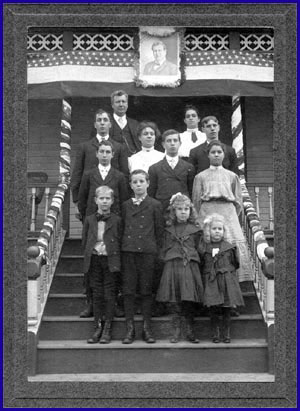

William and Agnes Wilson with their children:

First row (L – R) James, Joseph, Elizabeth & Jessie

Second row (L – R) Tom, William & Mary

Third row (L – R) Hugh, Agnes & Adam

A daughter Nellie was born July 30,1888 & died August 23, 1891

Ferniegair Farm

The farmhouse at Wilson’s home, Ferniegair Farm

William B. Wilson was very respected for being fair and unbiased in his opinion and was often asked to give his opinion on different matters, not only by the miners but by businessmen as well. A group of men noticed outcroppings of coal between Blossburg and Arnot and decided they should mine the area. They consulted several people, Wilson included. Each advised mining the property except Wilson. His report was that the veins were so located that it would not pay to work them. However, the men purchased the property and tried to mine it.

After a short time it was found that W.B. Wilson’s opinion had been correct and the mine was shut down. The owner of the property stated that as Wilson had given him good advice and the property was no good developing for coal, he would let him work it and share the profits. The property had a farmhouse and outbuildings with 100 acres of land. The price of the farm was $1,500. The farm, which Wilson named Ferniegair for a small town near his birthplace in Scotland, was hilly, with only a few acres suitable for tilling. The bottom lands were covered with broken boulders and the mountain pasture divided by a vein of sandstone. The neighbors joked about the cows falling off the farm and being killed.Wilson said, “We farm our lawn. We have none too much land, and we have deemed it better to work the good land than to try to keep up the lawn.”

After William’s death in 1934 the farm was sold to the American Legion Post No. 572 of Blossburg in 1937. The Legion Post is still located there today.

United Mine Workers Pins and Ribbons

Poetry

MEMORIES

by W.B. Wilson

Some poetry from Memories printed in 1916. I read them all and tried to pick one to send you, but it went to four, plus the words from the Dedication and Preface. MY FATHER’S DAY DREAM takes him back to Scotland, his memories there, then of the ride to the U.S. on the ship and finally, as he opens his eyes of the hills and fields of Pennsylvania. Next is THE COAL MINER. Life as a miner was tough and he set about trying to improve it. Next is LINES ON LEAVING HOME WHEN BLACKLISTED and his love for Agnes. And last, I had to include BLUE EYES which I presume were the color of Agnes’ eyes. BUT there is a legacy here – my dad, my sister, and I and my children all have blue eyes.

— Bob Wilson (great grandson), 11/20/99, via e-mail to Dave Jones (great grandson) Poetry written by William B. Wilson

MEMORIES © 1916, W. B. Wilson

DEDICATION

To my Father and Mother, whose hopes that their son might follow a literary career have not been realized, this little book is affectionately inscribed as a partial compensation for their disappointment.

WILLIAM BAUCHOP WILSON

Christmas, 1902

PREFACE

I have no intention of inflicting upon the general public these few rhymes, written, principally, under the influence of youthful exuberance. It could not be expected to appreciate the circumstances under which they came into existence or overlook the defects they contain. I am looking for a more sympathetic audience. This little volume has been printed (not published) for circulation amongst those intimate friends of mine who can bury its poetical, grammatical and structural defects beneath their personal respect for the author. My friend, Sam, says: “No man ever writes poetry except when his liver is out of order.” This may be true, and, if it is, I submit this book to my friends as conclusive proof that my life has been a reasonably healthy one.

THE AUTHOR

MY FATHER’S DAY DREAM

One evening last June when the day’s work was over,

I sat all alone in my cozy arm chair,

And drank the perfume of the sweet-scented clover

That floated along on the cool, balmy air.

My trusty clay pipe ‘tween my thumb and forefinger

I puffed with a lazy, luxuriant ease,

The smoke curling up for a moment to linger,

Then fade from my sight as it mixed with the breeze.

And as I sat thinking, the smoke curling o’er me,

There rose up a mirror-like vision of yore,

The land of my fathers lay plainly before me-

A beautiful picture from memory’s store.

Yes, there stood the mill, ‘neath the wide spreading rowans,

The miller’s neat cot on the brow of the hill.

I saw the broad fields dotted over with gowans

And heard once again Avon’s murmuring rill.

Bathed my hot limbs on its cool, rippling bosom,

Roved through the woodlands that rise from its side,

Plucked the bluebell and the hawthorn blossom

That flourish so full on the banks of the Clyde.

Gathered the woodbine and fragrant wild roses,

The daisy, the primrose and sweet heatherbell.

Chased the wild bee from its place on the posies

And searched for birds’ nests on the trees in the dell.

There by the road stood the one-story houses,

The thin strip of woodland just over the way

Where the robin, the sparrow and little titmouses

Were chirping their praise to the glorious day.

And far up the hill with the stone wall around it

The high park in glory looked down on the plain,

While the stately old oaks in the center resounded

With winds that to fell them blew fiercely, but vain.

I saw there the deer when the cannon’s loud rattle

Re-echoed like thunder o’er valley and hill,

Gallop off then come back, form like soldiers in battle,

Gaze wild at the cannon, excited but still,

Till another report sent them off in a hurry,

A frightened, excited, disorderly train,

Away round the hill in a terrible flurry

Then back through the same old maneuver again.

And here, too, the native white cattle came bounding

Out through the dense wood with a wild savage grace,

The forest behind them with echoes resounding

Of huntsmen and dogs that took part in the chase.

I thought of the time when the forest extended

O’er nearly the whole of old Scotia’s domain,

When cattle and deer from the mountain descended

To crop the luxuriant herbs of the plain.

When Wallace ere yet his fond hopes had been blighted

By cruel oppression’s dire death dealing sting,

In hunting the game of his country delighted,

Content in the shade of oblivion’s dark wing.

But the scene seemed to change to a ship on the ocean

Bound far to the West with its cargo and crew.

I gazed from its deck with a heartfelt emotion,

As slowly old Scotia receded from view.

And when the last trace of her outline was fading,

I stood on my tip-toe with uplifted hand

Laid over my temples, my strained vision shading,

To catch one more glance of my dear native land.

Then out from my dreaming the vision before me

Like Scotia’s sweet shore faded slowly away;

A dull, heavy feeling of sadness came o’er me,

And deep in my heart’s inmost recesses lay.

True, there stood Penn’s forest as stately as ever,

And, there, the wide meadows and tall growing grain,

And down in the valley the swift flowing river

Fast winding its way to the billowy main.

Yet though my heart loves them with loyal devotion,

My memory dwells on sweet visions of yore,

And pictures that country far over the ocean,

The land of my fathers, old Scotia’s loved shore.

MEMORIES index:

• The Coal Miner

• Lines On Leaving Home When Blacklisted

• Blue Eyes

Blue Eyes

by W.B. Wilson

Agnes

BLUE EYES

There’s an exquisite something about her,

Some undefinable grace

Of spirit or form, that without her

Dear presence about the place,

Sends the covetous heartaches thronging

Each other in wild surprise,

That I can not control the longing

To gaze in her sweet blue eyes.

Such eyes: In their limpid beauty,

So pleasant and strong and true,

Urging me on, when duty

Seems more than my strength can do.

I toil, and deem it a pleasure,

Yet, pray that God may devise

For me a lifetime of leisure

To gaze in her sweet blue eyes.

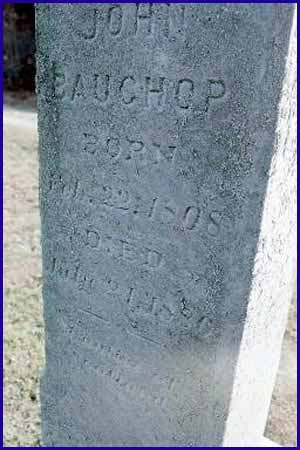

John Bauchop

The Blind Immigrant

Head stone of John Bauchop located in the Arbon Cemetery, Blossburg.

John Bauchop

Born Feb. 22, 1808

Died July 24, 1886

A native of Scotland

Webmaster’s note: I felt the following tale should be told as it is one of those little stories that are handed down by word of mouth from generation to generation within a family.

Many immigrants sold their homes and possessions in order to pay for their passage to America, only to be denied entry upon arriving because of health reasons. Their return passage cost them nothing but having sold everything to pay for the passage over there was nothing to return to. William B. Wilson was one of the young boys involved and it is ironic that as Secretary of Labor the Department of Immigration would fall under his jurisdiction.

John Bauchop was the father of Helen Nelson Bauchop Wilson, William’s mother. John had worked all his life as a blacksmith in Scotland. After years of watching the red hot coals of the smithy’s fire, he lost his sight. Although he was blind his eyes were clear, therefore no one could tell he could not see by looking at his eyes.

At the time he could not have legally come to America because of his blindness. When Helen and the children sailed to America, John was with them. During the passage from Scotland Helen’s two young sons would lead John along the ship’s deck one holding on to each of his hands. Everyone would see this and think that John was taking the young boys for a walk. John felt so comfortable being lead by the boys that when they landed in America no one questioned the elderly grandfather who was leading his two young grandsons one in each hand. Thus John Bauchop was able to get through the point of entry without being detected.

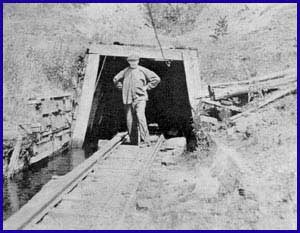

Arnot, Pennsylvania

where W.B. Wilson worked as a young miner.

Arnot

Bloss township, where Arnot is located, was taken from Covington township and named in honor of Aaron Bloss the founder of Blossburg. Its organization as a township took place in June of 1841. It originally encompassed the area which would eventually become Blossburg borough in August 1871, and a large portion of what would become Hamilton township in December 1871. In Bloss township in 1841 there were three different veins of coal underlying almost the entire township. The coal was of a semi-bituminous nature and the three veins became known as the Seymour, Bloss and Bear Run. The Bloss vein was the one that would be mined at Arnot.

Large deposits of coal were found along Johnson Creek, about four miles southwest of Blossburg. In order to develop the new coal field, the Blossburg Coal Mining and Railroad Company was formed and incorporated April 11, 1866. Members of the Corporation were Constant Cook, John Arnot, Charles Cook, Henry Sherwood, Franklin N. Drake, Ferral C. Dininy, Henry H.Cook and Lorenzo Webber. The corporation proceeded to purchase nearly the entire area of Bloss township and preparations were made for mining and marketing the coal.

A wagon road was built from Williamson Road to the coal openings two miles away to supply the site of a new village that was to be built. The new village was to be named Draketown, in honor of Franklin N. Drake the President of the coal company. In the summer of 1866 a railroad was completed between Blossburg and Draketown, as the No. 1 Drift was being opened. Later would come Drifts Nos. 2, 3, 4 and 5. A sawmill was erected at the location and Nicholas Schultz arriving in 1867 was placed in charge as head sawyer. At this time dwellings were built as well as a store. A year later a post office was built and the name was changed from Draketown to Arnot, in honor of John Arnot one of the incorporators of the company.

Arnot grew rapidly in population and was soon the largest town in Tioga county. By 1883 Arnot was at its peak in population with between 3,500 and 4,000 residents. Schools and churches were built and lodges and societies organized.

After the coal strike of 1899 things were not the same in Arnot. As in all industry, methods change, this was no exception in Arnot. The days of the drift miner were numbered as the cost of mining the coal was ever increasing. After the national coal strike of 1922 drift mining in Arnot gradually came to an end.

The coal company decided to sell Arnot to the residents of the town in 1952, for a price of $45,000. The amount of land conveyed was 562 acres, with a lot and house going for $500. Money received from the sale of any of the unused acreage is used to benefit the community.

There is no longer any heavy industry in Arnot and many of the residents travel to jobs in other areas of Tioga and Lycoming counties. According to figures from the 1995 census there are 390 residents of Bloss township. Today as you ride through Arnot the one thing that you can’t miss are all the new homes being built. Surely with the completion of Route 15 from a two lane highway to a limited access four lane through Tioga county the population of Arnot will increase.

Induction into the Department of Labor Hall of Fame

https://blossburg.org/wb_wilson/dol_induction.html

November 13, 2007

Washington D.C.

William B. Wilson was inducted into the US Labor Department’s Labor Hall of Fame at a ceremony which took place in the Great Hall of the Department of Labor in Washington D.C. on November 13, 2007. Wilson was chosen for this honor for his many years of work toward helping the wage earners of this country improve the quality of their lives.

The Labor Hall of Fame honors those Americans whose distinctive contributions to the field of labor have enhanced the quality of life of millions yesterday, today, and for generations to come.

Elevation to the Labor Hall of Fame is arrived at by a selection panel composed of the Counselor in the Office of the Secretary, the Solicitor of Labor, the Assistant Secretary for Policy and the Assistant Secretary for Administration and Management. Honorees are chosen each year, and a formal induction ceremony is conducted at the U.S. Department of Labor in Washington D.C.

The Labor Hall of Fame is located in the North Plaza of the U.S. Department of Labor, 200 Constitution Avenue, N.W., Washington D.C. The most recent honorees are represented by a kiosk containing a portrait, photos and memorabilia. The exhibit is open during regular working hours.

Bibliography

Our thanks and appreciation to those who have contributed their valuable time, photos, memories, newspaper clippings, and memorabilia to this project:

• David A. Jones, Blossburg, Pa. (great grandson)

• Robert Wilson, Annapolis, Md. (great grandson)

• Kitty Wilson, Blossburg, Pa. (wife of grandson Thomas Wilson)

• Jean Burnette Daugherty, Syracuse, N.Y. (grand niece)

• Janet Wilson Kirk Emerson, Convent Station, N.J. (grand niece)

• Susan Kaczynski, Blossburg, Pa. (great granddaughter)

• Sally Ward, Blossburg, Pa. (Blossburg Borough secretary)

• John Backman, Blossburg, Pa. (mayor)

• Heidi I. Jones, Blossburg, Pa. (great great granddaughter)

• Joshua D. Jones, Blossburg, Pa. (great great grandson)

• Beverly S. Jones, Blossburg, Pa. (wife of great grandson, David A. Jones)

• Shelly T. West, Laurel, Md.

• James McIntosh, Blossburg, Pa. (a life long friend)

• R. Keith Lindie, Blossburg, Pa. (a life long friend and photographic historian)

Source materials:

Babson, Roger W. William B. Wilson and the Department of Labor, (New York: Brentano’s) 1919.

Jones, Mary Harris The Autobiography of Mother Jones, (Chicago: Kerr Publishing Company) 1996 (original published 1925) Wilson, William Bauchop, unpublished manuscript, 1913.

Wilson, William Bauchop, Memories (Washington, D.C.: The Trades Unionist) 1916

Swinsick, Phyllis Flashbacks: The lore and legends of eight small communities in Tioga County, Pennsylvania, (Tioga County: Tioga Printing Corp.) 1993

The Blossburg Advertiser December 1898 through December 1899.

Many newspaper clippings, photographs, and oral histories. Most documentation available from David A. Jones.

The Wilson index:

- Coming to America

- Growing up in Arnot, Pennsylvania

- The Next 20 Years

- Secretary-Treasurer of the United Mine Workers of America

- Congress

- Secretary of Labor

- 1921 – 1934

- The Family

- Ferniegair Farm Blossburg, Pennsylvania

- United Mine Workers Pins & Ribbons

- Poetry By W.B. Wilson

- Bibliography

- Nov. 13, 2007 Labor Hall of Fame Induction