Growing up in Arnot

Wilson's Education

A few days after arriving in Arnot, Wilson and his younger brother Joseph were enrolled in the public school. Wilson's only education until this point was a year at St. John's Grammar School in Hamilton, Scotland, where he had been an excellent student. His father, who was barely literate, and his mother, who was educated, hoped to provide William with a formal education. Although he had to leave school shortly after he began, Wilson bought and borrowed books on an array of topics to increase his knowledge and to read aloud to his father. Adam had a strong interest in philosophy, history and economics, which provided Wilson with a strong foundation for understanding the world and the position of the miners. Having once earned two dollars doing odd jobs around the community, he bought a second-hand edition of Chamber's Information for the People and over the months that followed read it to his father.

Adam joined in the active debating sessions held in Hugh Kerwin's cobbler shop and Wilson, as his constant companion and fact-checker, accompanied him. Wilson wrote, "As I look back on the group of men that formed our little circle in the early days at Arnot, many of them classed as illiterate, I am still amazed at the knowledge they possessed of many religious, social, economic, political, historical and scientific questions, their wisdom and tolerance in discussing them, and their wide acquaintance with good literature. It was a splendid school for any boy to attend."

An avid reader, Hugh Kerwin kept a reading room and library in the back of his cobbler shop. Kerwin lent Wilson books from his library to take home and read. Wilson read every book in Mr. Kerwin's library, and still was not satisfied. With Kerwin's help, Wilson formed a library society and had the position of librarian, responsible for book selection and purchasing. Later, Wilson organized a debating society to gain public speaking skills. The club drew candidates for office during its political gatherings because it was known for the quality of its members' debates.

Wilson's democratic, capitalist political perspective was formed during these years. After gaining citizenship, Wilson's father chose the Socialist party, but Wilson did not follow because he felt the two available extremes of anarchy or socialism did not allow for the "fullest and best development of the human race if carried to their ultimate conclusion." Wilson strongly believed in the rights of the individual in a democracy and that those rights needed to be protected by government to ensure equal opportunity for all. He wrote, "Democracies are instituted for the purpose of giving to a majority of the people the power to determine [their collective future]...because it is recognized that certain things are purely individual in which no majority has any right to impose its will..." Wilson disagreed with the socialist stance of communal or state ownership of the means of production, believing that it inhibited individual development and expression.

Becoming a miner

Adam became ill with lumbago (a painful inflammatory rheumatism of the tendons and muscles of the lumbar region of the back) when Wilson was nine. He could still mine the coal but he could no longer pile it into the cars. Helen and Adam decided, with much regret, that Wilson should drop out of school to assist his father. Wilson loaded the coal into cars that his father had picked out of the rock while sitting on the mine floor. Eventually, his father taught him all aspects of mining. Wilson worked in the mine with his father for seven years.

In Nov. 1873, the mine owners cut wages, and then declared that the miners would not be allowed to cash in their company-issued script at the company stores until May 1874. The company stores would allow the workers to purchase up to their wages, but they could not have the remainder in cash. The farmers who sold their produce to miners were told they could only sell to the company stores. The farmers ignored the rule. The company then fired every worker who purchased from the farmers. At this point, the miners formed their first union, a local of the Miners and Laborers Benevolent Association. Only 11, Wilson joined as a half member. (Workers aged 16 and above were counted as full members.) The mine operators declared that no member of the union was permitted to work in the mines. The workers striked.

The company not only owned the means of production, but also the stores and the houses in which the workers lived with their families. The miners were evicted. Many stayed in Blossburg, the site of the nearest private, individually owned property. Throughout the mild winter, the miners continued to strike. They formed a store and worked with the farmers to bring food into the community.

Soon the rumor was passed around that the company was bringing in "Black Legs" to break the strike. One of the strikers was appointed to find the truth. And if it was true how would they come, from where and when. He reported that they were Swedes directly from Sweden, did not know a word of English and were coming by train. The miners had a meeting to decide how they would meet the "Black Legs". Among their number was one Swedish man, Otto Johnson, who could talk Swed, having been born and lived in Sweden. They persuaded him to meet the train and tell them the exact situation. This he did as the train stopped beside the platform that served as freight and passenger station at that time. As the conductor opened the door he stepped up and greeted them in their native language. He explained the situation and answered their questions. After hearing what Mr. Johnson had to say the Swedes decided they did not want to take any miners job. They took a vote and informed the train men they were going back, they would not "Black Leg". The company refused to return them on the train. The miners organized a band and lining up the Swedes, with Otto Johnson at their head and all the idle miners falling in, they marched the four miles to Blossburg. The miners helped procure work for most of them in machine shops, the foundry, the tannery and with farmers. The miners marched back to Arnot happy over a day well spent. By the beginning of March 1874, the company made overtures to settle. The strike/lockout was settled shortly, with the former wage rate and monthly paydays restored, the freedom to shop at non-company stores or with farmers re-established, and the houses reopened for occupancy. The Blossburg Coal Co. never tried to interfere with those basic freedoms again.

Later that year, Wilson decided to start a union for the boys who usually worked as trappers, opening and closing doors for ventilation in the mines. The boys followed Wilson's lead when their wages were reduced by 10 percent and decided to strike. Wilson wrote:

We found [the foreman] inside... the driver shanty with his back towards a huge fireplace, his head bowed and his hands folded behind him as though warming himself, although, of course being June, there was no fire in the grate. We hesitated at the door and then I led the way in and acted as spokesman. "Mr. Dunsmore," I said, "we have come to tell you that we are not going to accept the reduction in wages. We want the old rate back and if we don't get it we're going to strike." He slowly raised his head and looked at us, then his hands came from behind him and in his right one he held the usual mine foreman's yard stick. He caught me with his left arm and threw me over his knee and began to labor me with the yard stick. Every time he hit me with the stick he would exclaim, "I'll strike ye, ye beggar!"... The other boys all ran off to their respective working places and when Mr. Dunsmore got through striking, I declared the strike off. His argument had been forceful and effective, but it was applied to the wrong part of my anatomy to be permanently convincing.... It helped impress upon my mind the fact that until working men were as strong, collectively, as their employers, they would be forced... to accept whatever conditions were imposed upon them.

Wilson later concluded: "Ever since that day I have not believed in the use of force to settle labor disputes. Instead of the use of force, what we need is the spirit of justice, of fair play, that will result in a permanent industrial peace."

By 1876 there were only a handful remaining in the local union. With the decline in membership, Wilson was "pressed into service as secretary" of the local Miners' and Laborers' Benevolent Association. Wilson began to correspond with labor leaders around the country who expanded his knowledge and understanding of the labor movement.

The Wilson index:

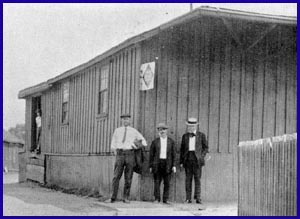

Cobbler shop owned by Hugh Kerwin (right) in Arnot, where Wilson formed a library and a debating society.

• William Bauchop Wilson Main Page

• Coming to America

• The Next 20 Years

• Secretary-Treasurer of the United Mine Workers of America

• Congress

• Secretary of Labor

• 1921 - 1934

• The Family

• Ferniegair Farm Blossburg, Pennsylvania

• United Mine Workers Pins & Ribbons

• Poetry By W.B. Wilson

• Bibliography